Samkhya and Yoga: Realization Of Self

Introduction

The Samkhya Yoga schools of philosophy are two distinct but closely related schools within classical Indian philosophy. While they have some differences in emphasis and approach. Both are intimately connected, with Samakhya. Providing the theoretical foundation and Yoga offering a practical path for the realization of the philosophical principles outlined by Samkhya. The two systems complement each other, combining philosophy and practice to guide individuals on a journey toward self-realization and liberation. Thus the discussion on these two should be parallel. Here are some key points of connection:

Common Foundation

Both Samkhya Yoga schools trace their roots to the ancient Indian sage Kapila. While sage Patanjali elaborated yoga practice Kapila’s teachings are traditionally regarded as the foundation of both systems.

Metaphysical Basis

Samkhya and Yoga share a common metaphysical framework. Samkhya is primarily concerned with the analysis of the fundamental components of existence, identifying the universe’s ultimate reality as consisting of Purusha (consciousness) and Prakriti (matter). Yoga, as systematized by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras, also acknowledges the importance of Purusha and Prakriti in its metaphysical framework.

Role of Purusha

In both schools, Purusha represents the eternal, unchanging aspect of reality—pure consciousness or the individual soul. The liberation (moksha) in both systems involves the realization of the true nature of Purusha and disentanglement from the influence of Prakriti.

Prakriti and the Gunas

Samkhya identifies prakriti as the primal, creative force that gives rise to the material world. Yoga acknowledges prakriti as well, and both schools recognize the three gunas (modes of nature) – sattva (goodness), rajas (passion), and tamas (ignorance) – as integral to the functioning of the material world.

Pathways to Liberation

While Samkhya is primarily a system of theoretical knowledge, Yoga provides a practical framework for achieving the goals of Samkhya. The Yoga school, as outlined by Patanjali, prescribes an eightfold path (Ashtanga Yoga) as a systematic approach to attain self-realization and liberation.

Ethical and Behavioral Guidelines

Both Samkhya and Yoga provide ethical guidelines for living a virtuous life. The yamas and niyamas, outlined in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, offer a code of conduct that aligns with the principles found in Samkhya.

Now let us discuss them in detail separately.

Samakhya School

It is believed to be the oldest school of Indian philosophy, referenced in many ancient Indian literature works. One such reference from Shrimad Bhagwad Geeta draws parallels in the Samkhya school and Yoga school of Indian philosophy. Samkhya serves as the foundational doctrine, outlining the theoretical principles that underpin the behavioral and practical aspects embodied by Yoga.

Attributed to Kapil Muni, acknowledged in Puranas as one of the 24 incarnations of Lord Vishnu, Samkhya is regarded as one of the most scientifically oriented schools of philosophy. Its alignment with numerous modern scientific concepts distinguishes it within the philosophical landscape.

In stark contrast to prevalent philosophical schools, Samkhya boldly rejects the notion of a creator or creation as the origin of the universe. Instead, it accentuates the concept of evolution, marking a distinctive and rational perspective on the cosmos.

It says that something will never come from nothing (satkaryavaad). It is the potential or probability that when it comes to reality is termed as a new creation. But which in reality is an actuation of the already present potentiality (Prakriti is Aja). It may be understood as anF analogy of the seed and the tree. The seed is seen as a potential that when met with required favorable conditions will eventually become the tree (reality). So rather than terming the tree as a new creation samkhya said it to be the evolution of the seed.

Kapila Sutra

It is believed to be the oldest of its literature which is lost in time. But its references are taken from various other ancient Indian literature. The modern samkhya is based on Ishwar Krishan’s work (Samkhyakarika) which derived its doctrine from causal theory (karya-Karan). Gautam Buddha extended this doctrine from the physical world to the social life of a man i.e. the Karma-Fal theory.

There are two types of causes in the world: the Upadaan – material cause (soil) and the Nivit – creative cause (potter). Both are needed for a potential to be manifested (pot). The properties of such reality depend upon the virtue (Gun– Sattva, Rajas, Tamas) of potential (seed).

According to Samkhya thought matter is made up of two fundamental elements (tatva) named Prakriti and Purusha. Together they form the basis of reality and are absolute and independent.

Prakriti (called bhogya)

Purush (called bhogta)

It is characterized as pure consciousness, devoid of attributes, qualities, or modifications. There are multiple individual Purushas, each existing independently. These individual Purushas are distinct, non-material entities, and are infinite in number (Anant). Every living being is associated with an individual Purusha. Although devoid of fundamental virtues (Nirgun) it contains intentionality of the consciousness i.e. of being aware (Chetna).

According to Samkhya, the universe evolves from the interaction of the three gunas in Prakriti. The evolution involves the emergence of the subtle elements (tanmatras), the gross elements (mahabhutas), and the creation of the material world. The reality we see is the product of the interaction of Purush and Prakriti where Purush is the light illuminating the already present, infinite, virtuous prakriti, but they never fully merge.

The ultimate goal in Smakhya’s thought of the individual is attaining a state of transcendence and liberation from the cycle of birth and death. The Samkhya school outlines a path to achieve this liberation, often referred to as kaivalya through the acquisition of knowledge (praman) and realization (by purusha) of its eternal, unchanging nature and disentangling itself from the influence of Prakriti.

Matter and motion were considered different things in classical physics and were the basis of Newton’s laws. But where does this motion come from? For this Newton had said, “God moved the universe and exhausted”. Modern physics, particularly in the framework of quantum mechanics, has provided insights into the nature of matter and has confirmed that motion is an inherent property of particles at the atomic and subatomic levels.

Sankhya also considers Rajas (motion) as the inherent virtue of Prakriti (matter).

Yoga school

The term “yoga” is polysemic. It means union which signifies the spiritual union of the individual soul with the universal soul. Yoga is defined as such by Adi Shankaracharya whereas sage Patanjali termed yoga as something that drives one towards samadhi (Yuj Samadho), which represents a state of profound inner peace, self-realization, and liberation (moksha) from the cycle of birth and death (samsara).

Yoga believes one can achieve salvation by combining meditation and the physical application of yogic techniques. It emphasizes discipline (anushasan) rather than knowledge/ curiosity (jigyasa). Its foundational text is the Yoga Sutras attributed to the sage Patanjali, who defined yoga as a means for chitta vritti nirodha meaning the cessation or control of the fluctuations of the mind, which leads to a state of mental stillness and clarity. To understand the process let us first understand Chitta.

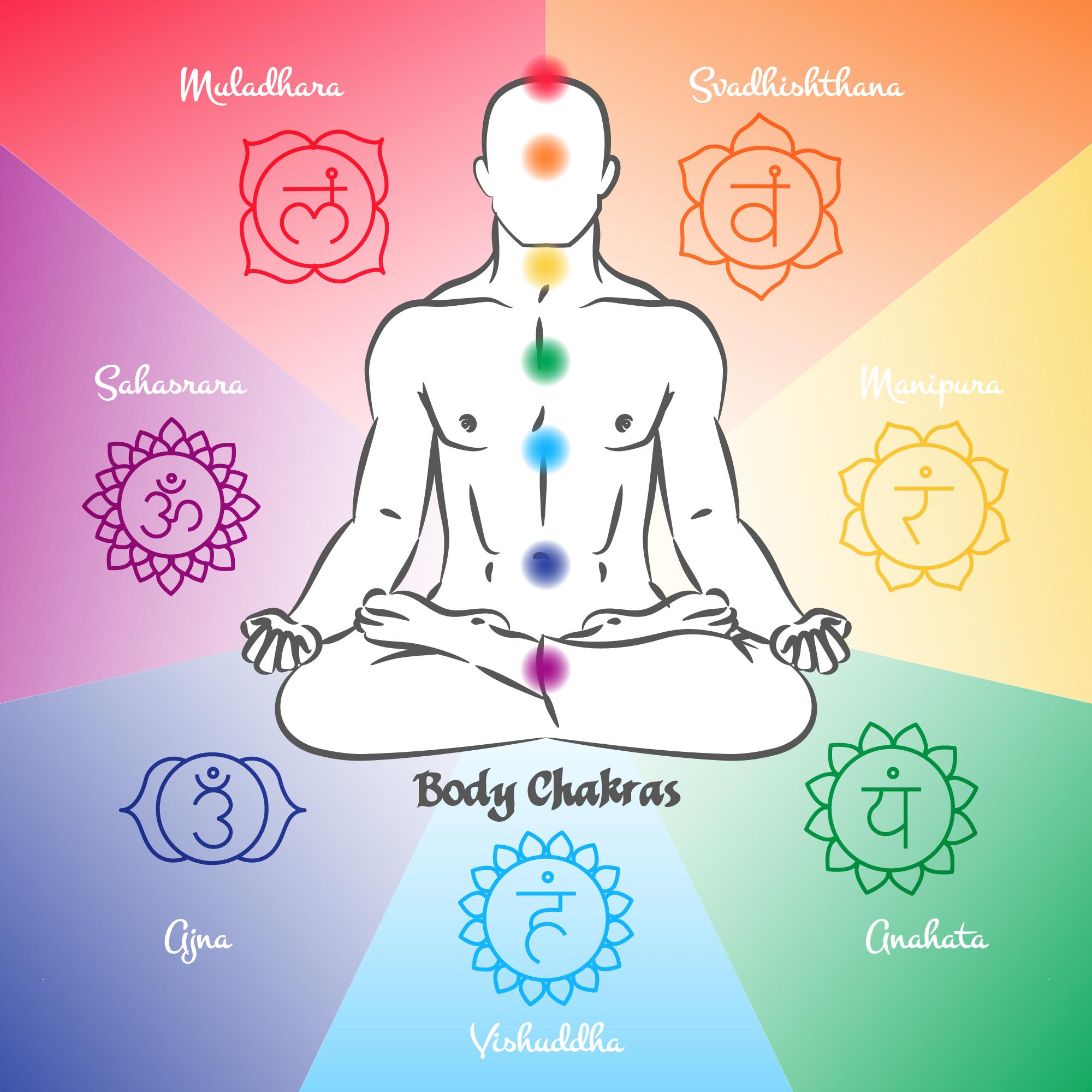

The union of Purusha and Prakriti gives Mahat (buddhi) tattva which further translates to ahankar(ego) and manas(man, mind). These 3 organs make Chitt (consciousness, Antahkarana).

Chitt is the first manifestation or differentiated form of Prakriti and is in itself unconscious but being nearest to purusha it appears conscious as its reflection. Like water Chitt takes the form of the object it is related to (Chanchalta). This form is called a modification of Chitt (Vritti). Chitta Vrittis encompasses all mental activities, thoughts, feelings, and impressions that arise in the mind. As Chitt reflects purusha, purusha also identifies itself with its reflection and appears to be changing.

Here chitta which is unconscious appears to be conscious and purusha which can’t be altered appear to change in influence of each other signifying Vrittis.

Patanjali categorizes chitta Vrittis into five types:

Pramana (Satya Gyan)

Pramana refers to the mental fluctuations associated with correct knowledge or valid perception. When the mind is engaged in a clear and accurate understanding of the external world, it is in the state of pramana.

Viparyaya (Mithya gyan)

Viparyaya involves mental fluctuations related to misconception or incorrect understanding. It occurs when the mind interprets information inaccurately, leading to false beliefs or misperceptions.

Vikalpa (Imagination)

Vikalpa represents the mental fluctuations associated with imagination, conceptualization, or fantasy. It involves the creation of mental images, ideas, or scenarios that may or may not correspond to reality. While imagination is a natural aspect of the mind, excessive Vikalpa can lead to distraction and unrest.

Nidra (Sleep)

Nidra refers to the mental fluctuations related to the state of sleep or unconsciousness. While asleep, the mind is not actively engaged in external perceptions or thoughts. Managing the nidra Vrittis is essential in maintaining conscious awareness and preventing the mind from becoming dormant or dull.

Smriti (Memory)

Smriti involves the mental fluctuations associated with memory or recollection. It includes retrieving past experiences, knowledge, and impressions stored in the mind. While memory is a valuable function, excessive attachment to memories can lead to emotional disturbances.

To develop a way to cease this modification of Chitt one has to understand its states i.e. the levels of Chitt Vrittis.

Ksipta (Distracted or Agitated)

In the Kshipta state, the mind is highly agitated and scattered. Thoughts are inconsistent, and the mind easily wanders from one idea to another. It is characterized by a lack of focus and restlessness.

Mudha (Dull or Stupid)

The Mudha state is characterized by dullness, lethargy, and a lack of clarity. In this state, the mind is sluggish, and there is difficulty in grasping or retaining information. The practitioner may feel mentally dull and uninspired.

Vikshipta (Partially Concentrated)

Vikshipta is a state of partial concentration. The mind fluctuates between periods of concentration and distraction. While there is some focus, the mind is still easily influenced by external stimuli and internal thoughts.

Ekagra (One-Pointed Concentration)

Ekagra is a state of concentrated focus where the mind becomes one-pointed. In this state, the practitioner experiences a deep level of concentration, and distractions are minimized. This is a preparatory stage for the higher states of concentration

Niruddha (Complete Restraint)

Nirodha is the state of complete restraint or control over the fluctuations of the mind. It is the ultimate goal in Yoga, where the mind achieves stillness and tranquility. In Nirodha, the practitioner attains a state of meditation and is absorbed in the object of concentration.

These Vrittis cause kleshas which are as follows:

Avidya (Ignorance)

Avidya is the fundamental klesha, representing ignorance or lack of true knowledge. It is the root cause of other afflictions. Avidya involves misunderstanding the nature of reality, including the true nature of the self (Atman) and the identification with the ego. Overcoming avidya is crucial for progressing on the spiritual path.

Asmita (Egoism or I-am-ness)

Asmita is the klesha related to egoism or the sense of “I-am-ness.” It involves the identification with the individual self (ego) and the tendency to see oneself as separate from others. Overcoming Asmita involves recognizing the unity and interconnectedness of all beings.

Raga (Attachment or Desire)

Raga is the klesha associated with attachment and desire. It involves an excessive clinging to pleasurable experiences and possessions. Overcoming raga requires developing detachment and cultivating contentment independent of external circumstances.

Dvesha (Aversion or Aversion)

Dvesha is the klesha related to aversion, hatred, or repulsion. It involves a strong dislike or avoidance of certain experiences, people, or situations. Overcoming Dvesha involves cultivating equanimity and accepting both pleasure and pain with detachment.

Abhinivesha (Fear of Death or Clinging to Life)

Abhinivesha is the klesha associated with the fear of death and clinging to life. It involves a strong attachment to one’s existence and a fear of the unknown. Overcoming Abhinivesha requires recognizing the impermanence of life and understanding the cyclical nature of existence.

There are means according to yoga to overcome these Kaleshas which are

Mudit (Joyful Satisfaction)

Mudit refers to a state of joyful satisfaction or contentment. It involves finding happiness and fulfillment in one’s current circumstances and being appreciative of the positive aspects of life. Practicing Mudit encourages a positive and grateful attitude, fostering a sense of joy regardless of external conditions.

Maitri (Loving-Kindness)

Maitri is the practice of loving-kindness and friendliness toward oneself and others. It involves cultivating a compassionate and benevolent attitude, extending goodwill and kindness to all beings. Maitri is a foundational principle in practices like Metta meditation, where one consciously sends thoughts of love and well-being to oneself and others.

Karuna (Compassion)

Karuna is the quality of compassion, which involves a deep awareness of the suffering of oneself and others and a genuine desire to alleviate that suffering. Practicing karuna means cultivating empathy, understanding the pain of others, and actively seeking ways to contribute to their well-being. Compassion is central to many spiritual and ethical traditions.

Upeksha (Equanimity)

Upeksha is the practice of equanimity or impartiality. It involves maintaining a balanced and even-minded approach to situations and people, irrespective of favorable or unfavorable conditions. Upeksha encourages the development of mental resilience and the ability to navigate life’s ups and downs with a sense of inner calmness and detachment.

Satsang (Association with Truth)

Satsang translates to “association with truth” or “gathering in the company of the wise.” It involves being in the presence of those who inspire spiritual growth and enlightenment. Satsang can include attending spiritual gatherings, studying sacred texts, or being in the company of wise and enlightened individuals. The influence of Satsang is believed to uplift and guide practitioners on their spiritual journey.

The term “Chitta Vritti Nirodha” refers to the cessation of the modifications of the mind, allowing the practitioner to experience inner tranquility and focus. To achieve this yoga gives ashtanga marg which is as follows:

Yama (Restraints)

Yama consists of five ethical principles or moral restraints that serve as guidelines for how individuals should interact with the world. The five Yamas are:

- Ahimsa (Non-Violence): Practicing non-violence in thought, speech, and action.

- Satya (Truthfulness): Commitment to truthfulness and honesty.

- Asteya (Non-Stealing): Refraining from stealing or coveting others’ possessions.

- Brahmacharya (Celibacy or Moderation): Exercising moderation in all aspects, including sexual conduct.

- Aparigraha (Non-Attachment): Cultivating non-attachment to material possessions and desires.

Niyama (Observances)

Niyama consists of five observances or personal disciplines that individuals are encouraged to cultivate for self-purification and inner development. The five Niyamas are:

- Saucha (Purity): Maintaining cleanliness and purity, both physically and mentally.

- Santosha (Contentment): Cultivating contentment with what one has.

- Tapas (Austerity): Practicing self-discipline and austerity for personal and spiritual growth.

- Svadhyaya (Self-Study): Engaging in self-reflection and the study of sacred texts.

- Ishvara Pranidhana (Surrender to the Divine): Surrendering to a higher power or the divine.

Pranayama (Breath Control)

Pranayama involves various breathing techniques and exercises designed to bring awareness to the breath, control the breath, and harness the life force energy (prana) for physical, mental, and spiritual well-being. The practice of pranayama is considered a powerful tool for purifying the mind, increasing vitality, and preparing the practitioner for deeper states of meditation.

Asana (Physical Postures)

Asana refers to the practice of physical postures or poses designed to promote physical health, mental well-being, and spiritual growth. Patanjali defines asana as ‘sthira sukham aasanam’ which emphasizes the idea that a yoga pose should be both steady and comfortable. The more rigorous postures are defined in Hatha Yoga which aims to cultivate physical strength, flexibility, and balance. It prepares the body for meditation and self-realization.

Pratyahara (Withdrawal of Senses)

Pratyahara involves consciously drawing the senses inward, away from external stimuli. The senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell) are typically engaged with the external world, but Pratyahara encourages practitioners to turn their attention inward.

The practice of Vishayadoshadarshanam is used for Pratyahara, which involves withdrawing the senses and developing discernment or mindful awareness regarding the objects or subjects to which the mind is drawn. It suggests the need to observe and understand the potential drawbacks or limitations associated with sensory experiences, desires, attachments, or any engagement with external stimuli. By cultivating this awareness, individuals on the yogic path aim to navigate life with greater wisdom and detachment, fostering inner peace and spiritual growth.

Dharana (Concentration)

Dharana is the practice of focused concentration. It involves directing the mind’s attention to a single point or object, cultivating mental steadiness and concentration.

Dhyana (Meditation)

Dhyana is the state of sustained concentration, where the mind is absorbed in meditation without distraction. It leads to a deep, uninterrupted flow of awareness.

Samadhi (Union or Absorption)

Samadhi is the ultimate state of union, where the practitioner experiences a profound connection with the divine or the true nature of reality. It is a state of transcendence and self-realization.

The ultimate aim or objective of practicing Yoga is often described in terms of attaining Samadhi, which leads to Kaivalya, the state of ultimate liberation or isolation that describes the nature of the self (purusha), the distinction between the self and the material world (Prakriti), and the complete freedom that comes with realizing one’s true nature. Yoga is also used to attain siddhis (psychic powers) which although isn’t its ultimate aim but mere distractions in the way of attaining Kaivalya.

Although similar in philosophical features, Yoga describes God (Ishwar) as a special Purusha that is considered to be beyond the cycle of birth and death, unaffected by karma (actions), and the ultimate guide and supporter of all living beings whereas Samkhya denies or is unsure about the existence of some higher being.