Buddhism: The Moral Extremes & Ethical Regorism

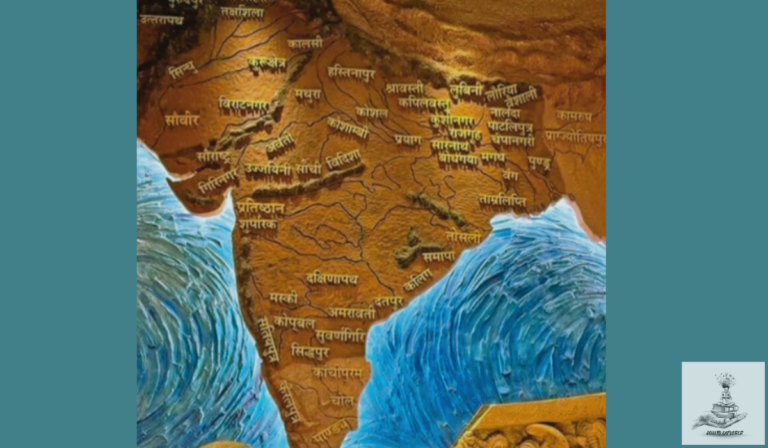

Our discussion on The Philosophical Epochs highlights various philosophical thoughts of India as well as of the world. In the Indian tradition of philosophical thoughts, various orthodox and unorthodox schools were enumerated. A brief discussion on unorthodox thoughts was also held. Today we are going to discuss one such unorthodox philosophical thought in detail, the Buddhist thought (Buddhism). The Buddha (the Founder of Buddhist thought) lived during a period of intense philosophical and religious exploration in ancient India (The Shramana Period). His teachings presented a unique perspective on various aspects of spiritual inquiry, including the role of the Vedas.

The Buddha talked harshly against the Vedic Karm Kaand and the opinion that violence in the name of Vedas (sacrifices) is allowed, was strongly discouraged by him. He argued that if something [The Vedas] can be deformed [by Brahamans] it can’t be universal thus there shouldn’t be a blind adherence to it [be any scripture or tradition]. He encouraged individuals to investigate and verify truths through their own direct experience. While the Buddha did not reject all aspects of Vedic thought, his emphasis on direct experience, ethical conduct, and the path to liberation distinguished his teachings from the prevalent religious practices of his time.

The Path Towards Buddha

The Buddhist thought is generally non-theistic, focusing on the nature of suffering, the path to liberation, and the cultivation of wisdom and compassion. While it does not deny the existence of deities or spiritual realms, the emphasis is on individual transformation and realization (Manavtavaad) rather than a relationship with a personal creator god. His teachings were more pragmatic and centered on understanding the true nature of reality (sat), and central to his thoughts are the Four Noble Truths, which form the foundation of Buddhist understanding and practice. The Four Noble Truths are

- Dukkha (suffering)

- Samudaya (origin/ cause)

- Nirodha (Cessation)

- Magga (the path)

Sarvam Dukkham (Dukkha/ suffering)

The concept of Dukkha in Buddhism refers to the inherent unsatisfactoriness or suffering that characterizes conditioned existence. There are three main aspects of dukkha:

Dukkha-dukkha (Suffering of Suffering): This refers to the inherent suffering or pain that is evident in certain experiences. It includes physical and mental pain, illness, aging, and death. Dukkha-dukkha encompasses the more obvious and direct forms of suffering that individuals encounter in life.

Viparinama-dukkha (Suffering of Change): This form of suffering arises from the impermanence (Anitya) of all things. Even pleasurable experiences are subject to change, and the joy they bring is temporary. This aspect of dukkha acknowledges that the very nature of conditioned existence involves the constant flux of situations and experiences.

Sankhara-dukkha (Conditioned or Pervasive Suffering): This is a more subtle and profound understanding of suffering. Sankhara-dukkha refers to the suffering inherent in all conditioned phenomena. It recognizes that everything in the conditioned world is subject to arising and ceasing, dependent on various causes and conditions. Even states of happiness or contentment within the conditioned realm are seen as ultimately unsatisfactory because they are impermanent and subject to change.

The Three Poisons of Buddhism:

Jara (Old age): Jara refers to the inevitable process of aging. It is a fundamental aspect of the human condition where the body undergoes physical changes, and individuals experience a decline in vitality and strength as they grow older. The recognition of aging as a form of suffering emphasizes the impermanence and fragility of the physical body.

Marana (Death): Death is another aspect of the Threefold Suffering. The cycle of life involves aging and eventual death, and this impermanence is considered a source of suffering. The fear of death and the uncertainty surrounding what comes after death contribute to the existential anxiety that individuals may face.

Vyadhi (Disease): Vyadhi refers to illness or disease. The experience of physical and mental afflictions, including sickness and suffering due to health issues, is considered a form of dukkha.

Physical ailments not only cause physical pain but can also affect mental well-being. Illness is seen as a reminder of the impermanence and the unsatisfactory nature of conditioned existence.

Understanding and contemplating the aspects of suffering is integral to the Buddhist teachings on the nature of existence and the path to liberation from suffering. The recognition of the unsatisfactory nature of these conditions is a key motivation for individuals to embark on the path of spiritual practice in Buddhism.

Samudaya (origin/ cause): Pratītyasamutpāda

Pratītyasamutpāda, often translated as Dependent Origination describes the interdependence and interconnectedness of all phenomena, emphasizing the contingent and conditioned nature of existence. It is typically expressed as a twelve-link chain (Nidana), illustrating the process of how ignorance leads to suffering and rebirth. The twelve Nidanas are

Avidya (Ignorance): Ignorance refers to a lack of understanding about the true nature of reality, particularly the Four Noble Truths. This ignorance leads to a distorted perception of oneself and the world.

Samskara (Volitional Formations/ Impressions): Ignorance gives rise to volitional formations (use of one’s will), which are mental activities or karmic formations. These are the intentional actions and thoughts that shape one’s karma.

Vijñāna (Consciousness): Volitional formations lead to the arising of consciousness. Consciousness, in this context, is the awareness or subjective experience that arises in conjunction with mental activities.

Nāmarūpa (Name and Form): Consciousness leads to the arising of name and form, representing the psycho-physical aspects of an individual. Nama refers to mental factors, and Rūpa refers to the physical body.

Ṣaḍāyatana (Six Sense Bases): Name and form lead to the arising of the six sense bases—sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mental perception. These are the avenues through which an individual interacts with the external world.

Sparśa (Contact): The six sense bases lead to the arising of contact, the interaction between the senses, their objects, and consciousness. Contact is a crucial step in the process of perception.

Vedanā (Feeling): Contact leads to the arising of feelings or sensations. Vedanā refers to the subjective experiences associated with sensory perception—pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral feelings.

Taṇhā/ Trishna (Craving): Feelings lead to the arising of craving. Craving is the desire or attachment to the pleasant, aversion to the unpleasant, and ignorance regarding the neutral. It is the emotional response to feelings.

Upādāna (Grasping): Craving leads to grasping or attachment. Individuals cling to desires and attachments, seeking to satisfy their cravings. Grasping involves a more intense form of attachment.

Bhava (Becoming): Grasping leads to the arising of becoming. Bhava refers to the process of taking on a new existence. The accumulated karma and attachments influence the nature of this becoming.

Jāti (Birth): Becoming leads to the arising of birth. Jāti refers to physical and mental birth into a new existence. This is the actual entry into a specific life form.

Jarāmaraṇa (Aging and Death): Birth leads to aging and death. The cycle continues as the individual undergoes the inevitable process of aging and eventually faces death. Aging and death set the stage for a new cycle of rebirth.

This chain illustrates the interdependence and causal sequence of conditioned existence. Breaking this chain is crucial in Buddhist practice, and the Eightfold Path is presented as a means to transcend this cycle by addressing the root cause of suffering—ignorance—and cultivating wisdom, ethical conduct, and mental discipline. Breaking the chain of dependent origination at any point is crucial for liberation. By eliminating ignorance and craving, one can cease the cycle of birth and suffering, reaching the state of Nirvana.

Nirodha: The Cessation of Suffering

Buddhism teaches about the four Brahmaviharas (Divine Abodes) i.e. the qualities or attitudes that, when cultivated, contribute to the development of a mind free from afflictive states to create a conducive inner environment for the deeper meditative practices that lead to the cessation of suffering. These qualities are considered as sublime states of mind that practitioners cultivate to develop compassion, loving-kindness, empathetic joy, and equanimity. The Four Brahmaviharas are

Metta/ Maitri (Loving-kindness): Metta is the practice of cultivating boundless and unconditional love and goodwill towards all beings. It involves wishing happiness, well-being, and safety for oneself and others. Metta is considered a foundation for developing other positive qualities.

Karuna (Compassion): Karuna is the quality of compassion or empathy, the genuine concern for the suffering of oneself and others. It involves a deep understanding of the nature of suffering and a sincere desire to alleviate that suffering.

Mudita (Sympathetic Joy): Mudita is the ability to rejoice in the happiness and success of others. It involves cultivating an unselfish joy that appreciates the well-being and good fortune of others without envy or jealousy.

Upekkha (Equanimity): Upekkha is equanimity or balanced mental state. It involves maintaining a sense of calm and impartiality in the face of life’s ups and downs. Upekkha is not indifference but rather a state of inner stability and acceptance, not swayed by attachment or aversion.

These Four Brahmaviharas are often practiced through meditation and are considered essential for developing a mind that is conducive to enlightenment. Practitioners often engage in formal meditation sessions to cultivate and strengthen these qualities, and they are encouraged to incorporate them into their daily lives.

Magga (the path): Dukkh Nirodh Pratripad Gamini

Buddhism gives an Eightfold Path (The Ashtanga Marga) that serves as a guide to ethical and mental development, leading to the cessation of suffering (Nirvana). It consists of the following components:

Right Understanding (Samyak Drishti): This involves developing a correct understanding of the nature of reality (Sat), especially the Four Noble Truths and the Three Marks of Existence (impermanence (Anitya), suffering (Dukkha), and non-self (Anātman)).

Right Intention (Samyak Sankalpa/ Acharan): It refers to cultivating wholesome and compassionate intentions. Practitioners aim to free themselves from attachment, ill will, and harmful thoughts, fostering a mindset of kindness, generosity, and renunciation.

Right Speech (Samyak Vac): This involves refraining from false, divisive, harsh, and idle speech. Practitioners strive to communicate truthfully, kindly, and purposefully.

Right Action/ Business (Samyak Karamant): It emphasizes living a moral and ethical life by avoiding harmful actions such as killing, stealing, and sexual misconduct. Right action involves cultivating virtues and positive conduct.

Right Livelihood (Samyak Ajivika): This pertains to earning a living in a way that is aligned with ethical principles and does not harm others. It encourages practitioners to choose occupations that contribute positively to society

Right Effort (Samyak Vyayama): This involves making a diligent and persistent effort to abandon unwholesome thoughts and behaviors while cultivating wholesome ones. It includes the development of mindfulness and awareness.

Right Mindfulness (Samyak Samriti): Mindfulness involves being fully present and aware of one’s thoughts, feelings, and actions. This awareness is cultivated through meditation and daily mindfulness practices.

Right Concentration (Samyak Samadhi): This refers to developing focused and concentrated mental states through meditation. Practitioners aim to attain deep states of concentration, leading to heightened awareness and insight. The practice of meditation is central to achieving the right concentration.

The Eightfold Path is often represented as a wheel, symbolizing the interconnectedness of its components. These are not sequential steps but are interrelated and mutually supportive. Practitioners work on developing all aspects of the Eightfold Path concurrently as part of their spiritual journey toward enlightenment.

The Threefold Training or the Three Higher Training representing ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom is given in Buddhism to walk the path towards liberation from suffering. Where Ethical conduct provides a foundation for mental discipline and wisdom, while mental discipline and wisdom, in turn, enhance ethical conduct. Together, they form an integrated path that leads to the realization of Nirodha, the cessation of suffering. These are

Sheela (Sila): This term refers to ethical conduct or moral virtue in Buddhism. It is one of the components of the Eightfold Path. Practicing good ethical conduct involves abstaining from harmful actions and cultivating positive behaviors. Sila is crucial for creating the foundation of a virtuous and harmonious life.

Samadhi: Samadhi refers to concentration or mental absorption, and it is another component of the Eightfold Path. It involves developing focused and concentrated states of mind, often through meditation. Samadhi leads to a deep, unified state of consciousness, helping practitioners gain clarity, tranquility, and insight.

Prajna (Panna): Prajna is wisdom or discernment. It is the third component of the Eightfold Path. This wisdom involves understanding the true nature of reality, seeing through the illusions of the self, and gaining insight into the Four Noble Truths. Prajna is often cultivated through mindfulness, meditation, and the study of Buddhist teachings.

The Concept of Nirvana

According to the Buddhist thought Desire and the cycle of birth and death is the root of all human suffering. Nirvana as the ultimate goal in Buddhism represents the cessation of suffering, freedom from the cycle of rebirth, and the realization of the true nature of reality. It involves the elimination of craving, attachment, and ignorance, leading to a state of profound peace and liberation. Nirvana signifies a deep understanding of impermanence, unsatisfactoriness & non-self and is to be realized through direct personal experience and insight. It may be defined in accordance with Buddhist thought as:

Extinguishing the Fires

Trishna (Craving): Nirvana involves the extinguishing of the fire of craving or desire. Craving is identified as one of the root causes of suffering, and Nirvana is the state where this craving is fully extinguished.

Dvesha (Aversion): The fires of aversion, hatred, or ill-will are also extinguished in Nirvana. The mind is free from the harmful mental states that contribute to suffering.

Moha (Delusion): Nirvana represents the eradication of ignorance and delusion. It is the state of clear understanding and insight into the true nature of reality, unclouded by ignorance.

Putting Out Ignorance

Avidya (Ignorance): Ignorance is considered the root cause of suffering in Buddhism. Nirvana is the state where ignorance is completely dispelled, and one attains profound wisdom and understanding of the nature of existence.

Prajña or Pragya (Wisdom): The cultivation of wisdom, understanding and insight leads to the extinguishing of ignorance. In Nirvana, there is a direct realization of the Four Noble Truths and the nature of reality as it is.

The Central Thought

The famous quote by Plato “A man is not known by the type of answers he gives but by the type of questions that he raises” greatly relates to the concepts (for understanding) of Buddhism. In Buddhist thought Man is the arbiter of his destiny [Karam Pradhan]. It asserts the middle path in the physical realm but extremes in Moral discipline accounting for the incorporated Ethical Regorism. Buddhism talks about understanding the nature of reality and the self through the three characteristics of existence, impermanence (Anitya), suffering (Dukkha), and non-self (Anātman).

The principle of causality is also closely linked to the concept of dependent origination [Pratītyasamutpāda] of Buddhism. The law of cause and effect is crucial in explaining the nature of suffering and the path to liberation. By understanding the causes of suffering and the conditions for its cessation, practitioners can follow the path to liberation, cultivating ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom to break free from the cycle of birth and death. The Buddhist thought emphasizes the interdependence of all phenomena and asserts that all things arise in dependence on other conditions and that understanding this interconnectedness is crucial for overcoming suffering. It asserts that the suffering (Dukkh) might be there but after walking the Eightfold path the consciousness (Chetna) of suffering ceases [Nirvana].